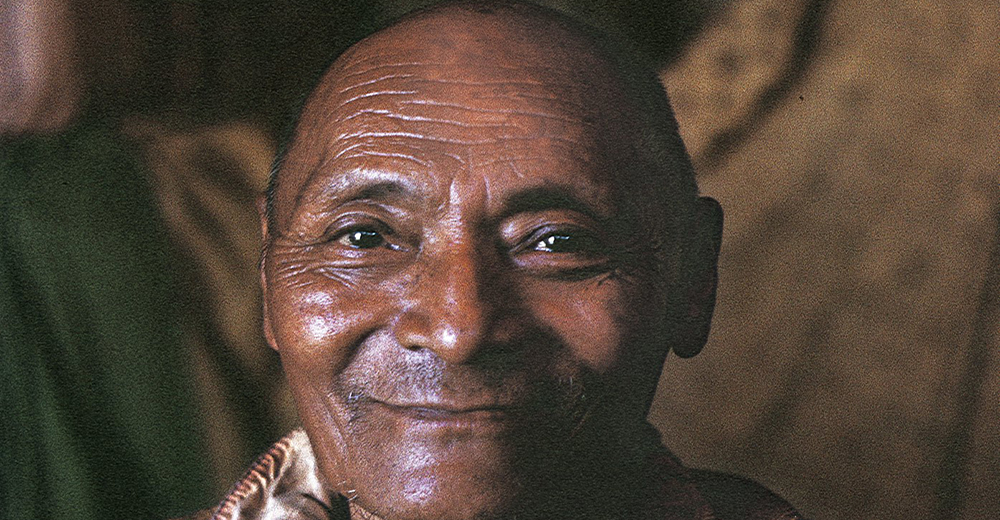

Kangyur Rinpoche. Photo by Matthieu Ricard

For the ancient Greeks, the word eudaimonia conveyed the notion of accomplishment, of flourishing, of deep long-term fulfillment. While pleasure corresponds to hedonism, happiness corresponds to eudaimonia. Similarly, in Buddhism, the word soukha refers to an exceptionally healthy state of mind that emerges from the cultivation of wisdom, compassion, and other fundamental human qualities.

Eudemonia or authentic happiness is not linked to a particular activity; it is a state of being, a profound emotional balance struck by a subtle understanding of how the mind functions. Ordinary pleasures are produced through contact with pleasant objects and end when that contact is broken, while lasting well-being, will be experienced as long as we remain in harmony with our inner nature. An intrinsic aspect of this flourishing is selflessness, which radiates from within rather than from focusing on the self. A person who is at peace with herself will contribute spontaneously to establishing peace within her family, her neighborhood, and, circumstances permitting, society at large.

In brief, there is no direct relationship between pleasure and happiness. This distinction does not suggest that we mustn’t seek out pleasurable sensations. There is no reason to deprive ourselves of the enjoyment of a magnificent landscape, of swimming in the sea, or of the scent of a rose. Pleasures become obstacles only when they upset the mind’s equilibrium and lead to an obsession with gratification or an aversion to anything that thwarts it.

Although intrinsically different from happiness, pleasure is not its enemy: it all depends on how the pleasure is experienced. If it is tainted with grasping and impedes inner freedom giving rise to avidity and dependence, it is an obstacle to happiness. On the other hand, if it is experienced in the present moment, in a state of inner peace and freedom, pleasure adorns happiness without overshadowing it.