M.R.: The worst yet is to imagine that we can be happy in an selfish way. A selfish happiness is fundamentally dysfunctional. Some imagine that they can build their happiness on the suffering of others, while our happiness must necessarily pass through the love and happiness of others. In Buddhism, there is a practice that consists in exchanging oneself for another. We look at ourselves as the other would, and we look at the other as if he or she were us. We can use the in-coming and out-going movement of the breath. When we breathe out, we think that we are giving all of the love, health, longevity, wealth, qualities, and knowledge that we have within us. We give ourselves fully, undivided, thinking that each being receives the totality of what we have. Then, we breathe in and take in with joy all the sufferings and difficulties of others, not as a burden but as a substance that we are able to dissolve, to transform. And so, love becomes as natural as breathing.

P.C.: That’s it exactly what we need: to love in order to live just as we need to breathe in order to live.

C.V-P.: You say that we cannot be happy without others. But then how do great meditators live for years in a cave without seeing or speaking to anyone?

M.R.: At the beginning, they notice within themselves a powerlessness to help others, and this makes them aspire to develop this universal love in order to be able to offer it more effectively. They are a little bit like a beggar who wishes to offer a feast to his friends without having the means to do so. During all the years that the great Tibetan hermit Milarepa spent in total seclusion, there was not one prayer, meditation, or mantra that was not dedicated to the well-being of others. This quiet solitude enables one to build a tremendous strength in order to accomplish the only worthwhile goal: to serve others — all sentient beings without exception. We can think that a meditative life is useless. When we build a hospital, the plumbing and the electrical and masonry work, these do not heal the sick. However, once the hospital is completed, it helps much more than if surgery had to be done in the street.

P.C.: In India, my prayers are about others, for others. I always strive to see what influence others have on my life. Some men have had an impact on my life, such as Mahatma Gandhi. Sometimes, we just need to meet someone for a few seconds for that person to determine the rest of our existence. It’s similar to two trains that cross one another. Of course, nowadays, in the West, trains go too fast, and we no longer have the time to look. In trains in India, I sometimes blow a kiss to someone who is in a train that is crossing mine, and I get a response. A long time ago, I met a beautiful 25-year old woman. Her name was Yvonne Tap, and she had come to India in 1950. Deeply moved by the destitution of the slums and shantytowns of Calcutta, she told me, ‟I have nothing to give them. So, I will give myself.” This woman had come to India for three months. She still lives here to this day. She became a Carmelite nun in a monastery in Bihar, one of the poorest states. I only saw her for a few minutes, but I will always remember it.

M.R.: I know someone who met his spiritual master for only a few minutes. It was as if a door had opened up within him. It was enough.

C.V-P: Do you suffer from being in solitude?

P.C.: Yes, this is my only suffering. I suffer from cultural solitude. This solitude does not come from heat, discomfort, or mosquitoes. And you, Matthieu, do you suffer from solitude?

M.R.: No (laughter). Moments of solitude are a real treat. They are like clay for the potter to fashion a pot.

P.C.: I still have a lot to learn. I am currently doing overtime in life so I can learn to love more.

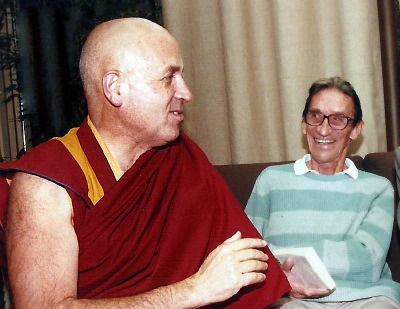

Photo Olivier Follmi

Photo Olivier Follmi