The Buddhist monk and bestselling author’s latest book tells the story of his spiritual journey. He discusses joy, suffering and how to foster happiness and health

Photograph: Magali Delporte/The Guardian

Interview by Emma Beddington, for The Guardian

I get anxious about interviews, I tell Matthieu Ricard moments after he appears on my computer screen in his red and saffron robes, his background, somewhere in the Dordogne region of France, discreetly blurred. He starts laughing uproariously before I can even get my confession out; he laughs frequently and infectiously throughout our call. “Really? In your job?” Yes, I reply. Does anything make him anxious? He considers the question. “Yes, missing planes or trains. Besides that, I don’t have many worries.”

This interview in particular feels intimidating. Ricard, 77, combines the rigour of a French intellectual (he has a PhD in cellular genetics, has written books on altruism, meditation and compassion for animals and translated numerous Buddhist texts into French and English) with the wisdom you get from 50-plus years of intense spiritual practice. I have the profundity of a Pop Tart and told a fruit fly to fuck off this morning; of course I’m anxious.

But I’m also excited. Like so many of us, I have spent most of my life wondering about happiness: is it really achievable? How? Is it selfish to even strive for it? Who better to help than “the world’s happiest man”? This millstone of a title –“a nonsense idea” he calls it – attached to Ricard after he took part in a 2004 research project that analysed his brain as he meditated on compassion. The electroencephalogram recorded unprecedented levels of gamma waves, associated with wellbeing and focus. His meditation also activated an area of the brain associated with positive emotions. “Just think for two seconds,” he says with gentle exasperation. “How can we know the state of happiness of 8 billion human beings? Maybe there’s a guy who’s in complete bliss all the time?” Does the label annoy him? “No. I feel embarrassed. One of my friends said: ‘On your grave it will read: ‘Here lies the happiest man in the world.’’” But his spiritual teacher’s grandson, he says, told him: “Take it and use it. Stop fighting it.”

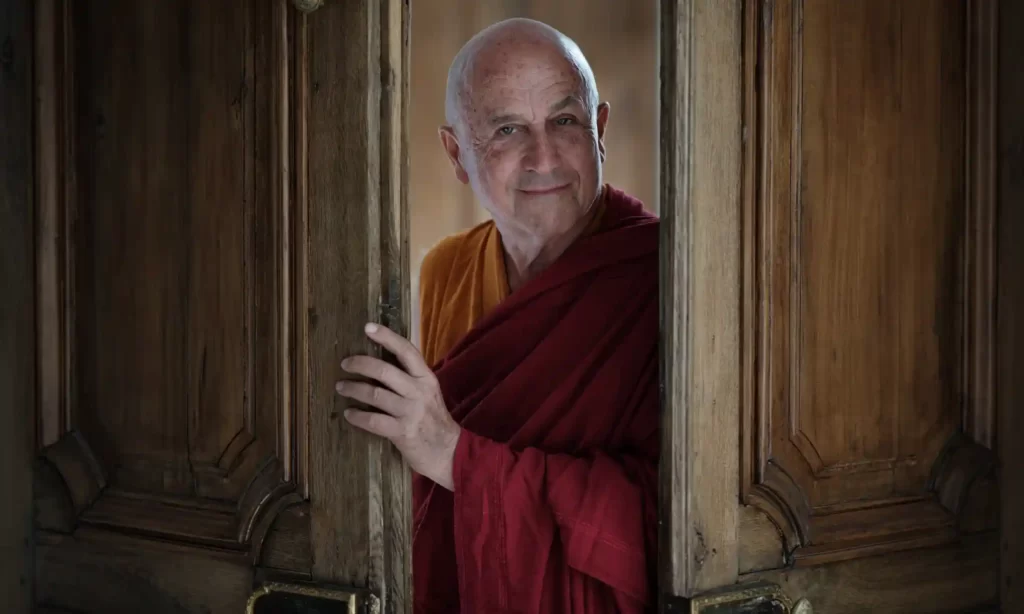

Matthieu Ricard lives in the Shechen Tennyi Dargyeling Monastery in Nepal.Photograph: Magali Delporte/The Guardian

And anyway, he did write a book called Happiness. “I wanted to call it Suffering,” he says, which makes me laugh, imagining his publishers’ faces, but for once he is deadly serious: “No! It’s true!” Real happiness, he explains (he calls it “eudemonia”, an ancient Greek term) comes from ridding yourself of sources of suffering: hatred, pride, jealousy and so on. This kind of wellbeing is “a sort of bonus” that comes from compassion, benevolence, altruism – and it is lasting and stable. You can feel it even in moments of grief and regardless of your material circumstances; he calls it “a way of being that pervades”. That distinguishes it from pleasure, which is “perfectly fine, but not happiness”.

I struggle with this part, I tell him. I see pleasure – small joys – as an accessible form of happiness: enjoying nature, my family, cake. That’s not bad, is it? There’s a hint of the professor he almost became, dealing with a dozy student, as he replies. “Of course not! There’s absolutely nothing wrong with taking a hot shower after walking in the snow. But if you stay 24 hours under a hot shower, you will not like it.” He could listen to a beautiful piece of Bach three times, he says, but not for 24 hours. Pleasure fades, becomes neutral or unpleasant or inaccessible when circumstances change, he says, while happiness, “the more you experience it, the more it gets deeper, vaster, resistant to circumstances. But there’s nothing wrong with pleasant sensations! It’s simply a different thing.”

I feel I’m bad at happiness; can that change? “Of course.” Our mind can be “our best friend or our worst enemy”, Ricard says: we need to cultivate qualities – “benevolence, inner strength, inner freedom so you are not too fragile for the ups and downs, discernment” – that mesh together to create eudemonia, and that’s a skill that takes practice. “Actually, it would be strange if that wasn’t the case. Why would this be the only thing in our human being that is fixed?” Some find it easier than others – he describes himself as “naturally inclined to serenity and rarely troubled by turbulent feelings” – but if you start from a low base, you are more likely to see a dramatic improvement.

But Happiness came out 20 years ago; it’s old news. Ricard’s latest book, Notebooks of a Wandering Monk, is all about his extraordinarily full life. He doesn’t like me calling it a memoir – he visibly bristles when I suggest it and says he is not fully at ease with his long-time publisher’s insistence on labelling it as such, preferring to call it “testimony”. He knows “some guy on Amazon who always writes terrible things” will laugh at a person whose faith focuses on the death of ego writing 800 pages of autobiography. But it does relate a personal as well as a spiritual journey, from long periods in remote Darjeeling, Nepal, Bhutan and 21 trips to Tibet, including one in 1985 as one of the very first outsiders allowed in following the Chinese invasion. There are stints interpreting for the Dalai Lama and speaking at Davos and the UN and collaborations with world-leading scientists (he has co-authored papers on the neuroscience of meditation). “I have met so many extraordinary people and seen so many fabulous things,” he says. That’s why he wrote the book. Otherwise “they are going to die with my brain.”

Ricard translating for the Dalai Lama in Paris in 2008. Photograph: Patrick Kovarik/AFP/Getty Images

Even the minor details are gripping: observing Tibetan yak herders, horsemen and hermits; encounters with Chinese bureaucrats or the Bhutanese royal family; perilous climbs to Himalayan mountain-top holy sites; an eyewitness account of his teacher’s “thukdam” (a period of death without decomposition). There’s a great anecdote about him refusing to kill the tapeworm he’s acquired, only for his spiritual teacher to force him to take the anti-parasitic, telling him “Drink! Your human life is more precious than that of a worm.”

Ricard grew up in France. His mother, Yahne le Toumelin, was a pioneering abstract painter (she also became a Buddhist nun in 1968), a protege of André Breton whose friends included Leonora Carrington and Luis Buñuel (Ricard mentions having lunch with Igor Stravinsky when he was 16). His father, the journalist and philosopher Jean-François Revel, edited the news weekly L’Express, published prolifically, and was a member of the Académie Française. But he describes his bewilderment, growing up, at how there appeared to be no correlation between genius and being a good person and the crystallising moment in the confusion and emptiness he felt when a friend showed him a documentary on Tibetan Buddhist spiritual leaders in exile (whom he describes as “20 Socrates or St Francis of Assisi”). “I thought OK, I’m going, let’s see.”

Ricard says he was “born on 12 June 1967”, at the age of 21 – the day he met his first teacher, Kangyur Rinpoche. He gave up a high-flying postgraduate position at the prestigious Institut Pasteur (founded by Louis Pasteur and home to 10 Nobel laureates, including Ricard’s supervisor François Jacob), said goodbye to the colonic bacteria that were the subject of his doctorate and moved to Darjeeling in 1972, before becoming a monk six years later. Was he apprehensive about telling his steely and intellectual father? “I hate big clashes,” he says. “Fortunately, that never happened.” His mind was made up and he was anxious to tell Revel “in a diplomatic, nice, loving way”. His father said little (though a friend later confided that he had cried). “He just said: ‘How are you going to make a living?’ It’s a good question, because I never even thought about that.”

‘My father asked me: ‘How are you going to make a living?’ It’s a good question, because I never even thought about that.’Photograph: Magali Delporte/The Guardian

I wonder if that was because of his bourgeois background but he corrects me: money was always tight, growing up. His father gave his mother very little (less still when they divorced); they were sometimes short on food and there were few toys for Christmas. He is surprised at how little material considerations crossed his mind, though: “It simply didn’t come into the equation.”

Does he wonder what life might have been like if he had stayed on his ordained Parisian path? Not really, he says. “As a friend says, you would be one of those proud scientists.” He went back to Pasteur many years later and talked to a close friend and lab neighbour who had been studying the regulation of the gene for maltose. “I asked him: ‘What are you doing research on?’ He was still working on that, 25 years later. We looked at each other and he laughed. He could see I was thinking: ‘Oh, poor you.’”

He does wonder, though, what might have happened if he hadn’t collaborated with his father in 1997 on the book that completely changed the trajectory of his life, The Monk and the Philosopher. “I would be in a cave or a hermitage for this past 25 years. Maybe I would have become enlightened, who knows?” The philosophical dialogue was a near-instant bestseller, catapulting him into a “maelstrom” of media appearances, planes, trains, writing and book promotion. Overwhelmed, he talked to one of his teachers, who advised him: “Accept everything.” He did. It might not have been the route he would have chosen, “But I can’t say I feel it was useless.”

People stop him in the street, saying: “You changed my life”; or sometimes: “You saved my life.” “You feel: ‘I didn’t mean to!’” he says. “You give them a hug or something, then we have to part.”

He has touched a “wide audience”: one day, he relates, a builder and a Ferrari driver both stopped him to thank him for his book on altruism. On top of that, royalties enabled him to start his Karuna Shechen charitable foundation, funding education, healthcare and environmental projects in India, Nepal and Tibet. “We help 400,000 people every year.”

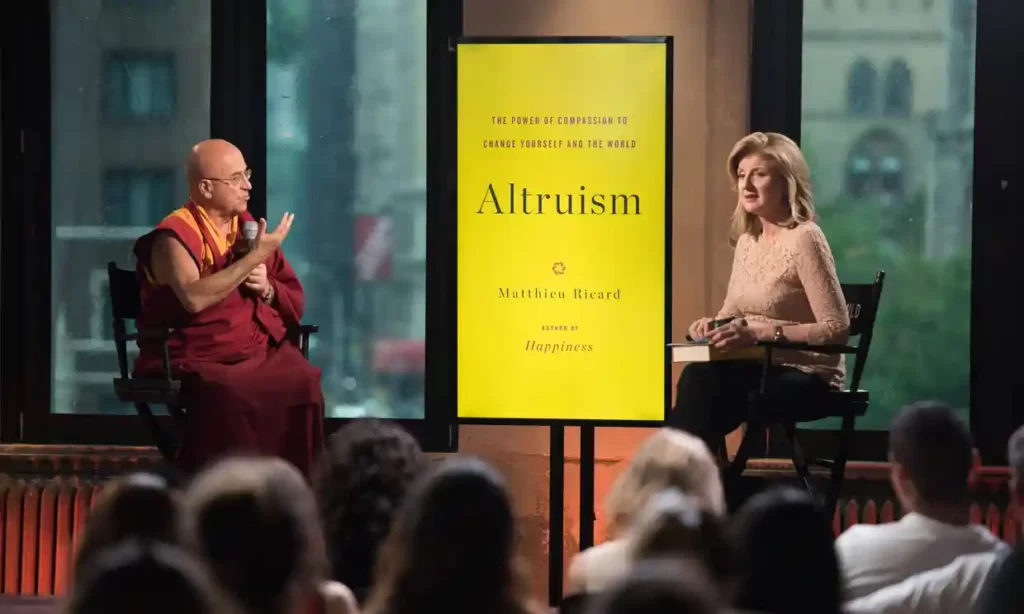

Ricard discussing his book on altruism in New York in 2015. Photograph: Dave Kotinsky/Getty Images

I wondered, reading this new book, whether he had felt the impact of the climate crisis in the remote, beautiful landscapes where he spends so much time and that he clearly holds so dear, recalling his ecstatic descriptions of the gentians in Tibetan meadows, the birds, the snow-capped peaks and thin clear air. “Oh yes,” he says, listing rivers flooding, mountains becoming black, moraines in Bhutan perilously close to breaking point. “There are 30,000 lakes in Nepal and Bhutan that have no names because they did not exist 30 years ago. For young people I understand it’s a source of anxiety; how could it not be?” The antidote is action: “Act with compassion, then you won’t feel so anxious. Do something, generate an attitude and get together.” Compassion and action need to go together, he says, in combating the climate crisis and in everything.

In some ways, the world in 2023 has adopted concepts close to Ricard’s heart: veganism and meditation are everywhere. I wonder how he feels about the contemporary cult of secular mindfulness – drained of spirituality, is it missing the point? “The Dalai Lama has said it’s very simplistic. It’s true that nowadays people present it like a panacea – it’s a bit like McMindfulness. If something becomes popular, it’s unavoidable. Sometimes it’s a bit annoying – they tell you how it should be.” But he knows Jon Kabat-Zinn, high priest of mindfulness, well, and believes he has made a positive difference in the world, relieving suffering. “He never pretended this is full-fledged Buddhism. If a tool is useful, it is useful.”

The new book marks the closing of a chapter for him. Ricard wants to get back to translation (there’s an 800-page Tibetan text on his desk) and to his spiritual practice: “I’ve clowned around quite enough.” The past four years have been anything but clowning though: he was “mummy-sitting”, as he calls it, in the Dordogne, caring for his mother, Yahne, who died this May. “My mother left in her hundredth year and we surrounded her with love at home. It was wonderful; I feel very fortunate. Now I will resume my wandering life.” He feels “a sense of being at ease” in Nepal, where his monastery is, and in the Himalayas generally more than in France. “I’m not very at ease with the French mentality – all this complaining all the time.” He will finally get back there in November, although first there is a documentary to film in Iceland on mental health and loneliness, and some photography (another one of his talents and “my favourite way of getting distracted”).

Fame and writing have taken him away from the life he chose when he was reborn in 1967, but he hopes and trusts there will still be time for everything. “I’m 77, in good health. I don’t believe in living 1,000 years – imagine 1,000 years of Trump! I’m not sure that is what we need – but if I’m lucky, a few more years to focus on what matters most.” What would he hope that people can take from his life and his writing? “Become a better human being to better serve others.” That’s what he would put on his grave, he says, not that being the world’s happiest man stuff. “I don’t think I will be buried – probably burned or given to the fish – but if I were, it would be that.”